Early medieval communities at Rendlesham

A vicus regius (royal settlement) at Rendlesham was first recorded by The Venerable Bede, a Northumbrian monk writing in the 8th century AD in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (History of the English Church and People):

"Swithelm, the son of Seaxbald, was successor to Sigeberht. He was baptized by Cedd in East Anglia, in the royal village called Rendlesham, that is, the residence of Rendil. King Aethelwold of East Anglia, the brother of King Anna, the previous king of the East Angles, was his sponsor."

Image: Extract from Historia Ecclesiastica, Book III, Chapter 22 from Cotton MS Tiberius C II by permission of the British Library

The christening Bede described probably took place around AD 660, which suggests that the royal settlement was at Rendlesham in the second half of the 7th century. The exact location of this royal settlement has eluded historians and archaeologists for centuries.

In the early 19th century a cremation burial in a pottery urn of 5th or 6th century date was found at Hoo Hill (RLM 006). Fieldwalking during the early 1980s recovered pottery sherds dating to the 7th - 9th century on fields between St Gregory’s Church and Naunton Hall. In 1982 a small-scale excavation nearby revealed Middle Saxon ditches, a Late Saxon ditch and pit (RLM 011). However, there was little to suggest a royal settlement.

Image: Illustration of Anglo-Saxon Urn from Hoo Hill (left) and pottery sherds recovered when fieldwalking (right)

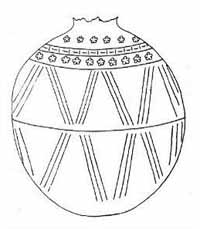

That all changed in 2008 when Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service began a programme of systematic survey and small-scale excavation. This work revealed a unique site in early England in its size, wealth and complexity; best paralleled by central places in contemporary Scandinavia. Some of the 7th century objects are of outstanding quality, made of gold with garnet settings and comparable to pieces found in the richest burials such as at Sutton Hoo.

The number of early medieval coins is also remarkable, making this one of the wealthiest sites of the period known in England. The food debris found in the excavation supports this, with the evidence of sparrowhawk suggesting the aristocratic sport of falconry and evidence of young cattle perhaps from feasting on expensive veal.

Image: Gold and garnet pyramid mount from a scabbard (left) and two beads from a necklace (right)

Many objects that suggest metalworking were found in one area. The evidence suggests highly skilled craft workers were producing dress fittings and jewellery in precious metals at Rendlesham in the late 6th and 7th centuries. All stages of the bronze working process are represented in the finds, including lead models for casting moulds, casting sprues, and discarded unfinished objects. The products include everyday objects such as buckles, pins and box fittings as well more elaborate pieces.

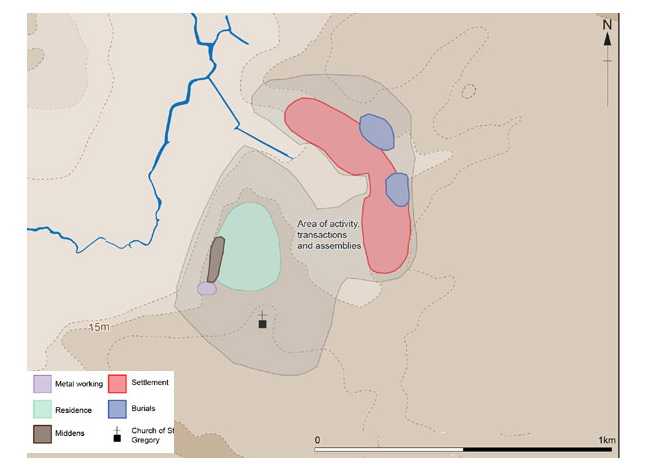

The early medieval finds covered about 50 hectares (120 acres). To the north, 5th to 6th century settlement and cremation burials have been confirmed by the test excavation. The metal detected finds also suggest inhumation burials. The main area of metal working evidence is to the south, near to the densest area of wealthy 7th century finds. Here the excavation confirmed that there are surviving layers of rubbish and features of this date, probably close to a high status residence, perhaps the possible large timber hall on the cropmarks.

Image: Interpretation of Anglo-Saxon activity at Rendlesham

Prehistoric and Roman activity at Rendlesham

While the early medieval finds may be the most significant, they make up only 24% of the total objects from the metal detecting survey. There is a background of later prehistoric activity, as one might expect along a major river valley, including worked flints, occasional pottery sherds and a few possible small enclosures in the magnetometry results. A larger D-shaped enclosure was Iron Age, backfilled in the mid-1st century. At least three Roman sites have been identified from the finds, two being probable farmsteads in use throughout the Roman period but abandoned before the 5th century. The third lies within the core area of early medieval activity and the type of finds might suggest an official presence here in the late 4th and early 5th centuries.

Image: Prehistoric flint (left) and a Roman mount (right)